Blog & Latest Updates

Fly Fishing Articles

Insects by Common Name

Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun)

Taxonomic Navigation -?-

Kingdom

Animalia (Animals)

» Phylum

Arthropoda (Arthropods)

» Class

Insecta (Insects)

» Order

Ephemeroptera (Mayflies)

» Species invaria (Sulphur Dun)

Common Names

Ephemerella invaria is one of the two species frequently known as Sulphurs (the other is Ephemerella dorothea). There used to be a third, Ephemerella rotunda, but entomologists recently discovered that invaria and rotunda are a single species with an incredible range of individual variation. This variation and the similarity to the also variable dorothea make telling them apart exceptionally tricky.

As the combination of two already prolific species, this has become the most abundant of all mayfly species in Eastern and Midwestern trout streams.

Where & When

The invaria hatch begins in early May in Pennsylvania. The Catskills peak in late May and early June, while mid-June is best in the Adirondacks and the northern fringe of the Upper Midwest.

Good fishing from this hatch usually lasts about two weeks in a particular location.

Hatching Behavior

Time Of Day (?): Flexible based on weather. Generally mid-afternoon at first and later as the season progresses.

Habitat: Almost anywhere, but best near fast runs and riffles.

Water Temperature: 52-60°F

Ephemerella invaria nymphs drift for some time just below the surface as they begin to emerge, and these floating nymphs cause rises to the surface which may fool the angler into thinking the trout are taking duns.Habitat: Almost anywhere, but best near fast runs and riffles.

Water Temperature: 52-60°F

Emergence itself takes quite a while, making emerger patterns more important for this hatch than for most. This importance is heightened by the lower availability of the fully formed duns. These duns take to the air more quickly than most of their Ephemerella kin, but anglers should still be prepared to imitate them if need be.

Spinner Behavior

Time Of Day: Dusk

Habitat: Riffles

Duns typically molt and return to the water as spinners within one day. The females drop their eggs in mid-air and are not exposed to trout until they fall spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.)--if they fall spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) at all. Habitat: Riffles

Knopp & Cormier write in Mayflies: An Angler's Study of Trout Water Ephemeroptera that the males seldom fall spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) on the water and the females only fall sometimes. Ted Fauceglia's Mayflies says both genders fall spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) on the water. This disagreement mirrors the confusion I've felt about this species on the stream; the spinners are generally unpredictable, but they can provide excellent fishing.

Nymph Biology

Current Speed: Usually medium to fast, sometimes slow

Substrate: Many types, but gravel is preferred

Environmental Tolerance: Unlike Ephemerella subvaria, invaria is very tolerant of a wide range of conditions.

These are among the most adaptable of mayflies, thriving in many types of habitat. They inhabit warmwater streams as well as cold and are found up and down the channel in riffles, pools, and runs. They are most prolific in deep, gravel-bottomed riffles.Substrate: Many types, but gravel is preferred

Environmental Tolerance: Unlike Ephemerella subvaria, invaria is very tolerant of a wide range of conditions.

In the days and hours before the hatch these nymphs become especially active, so their imitation is especially useful. They clamber to better emergence sites where they rest in plain view of both trout and photographers (see my underwater photos). They also make apparent "practice runs" to and from the surface in the manner of Ephemerella subvaria.

The nymphs are a little bit difficult to recognize because they their base color ranges from brown to olive and they're adorned with many possible color patterns. Anglers should be prepared with imitations in brown and olive, hook sizes 12 through 16.

Ephemerella invaria Fly Fishing Tips

Take extra care during emergence to figure out if the trout are feeding on floating nymphs, emergers, or duns, and what size Sulphur they are taking. The invaria duns can be hook size 14 or 16. The possibility of confusing them with the smaller Ephemerella dorothea adds to the Sulphur challenge. Remember that the solution to this puzzle may vary from fish to fish, and you should switch flies or switch fish quickly if what you're trying isn't working.

Pictures of 45 Mayfly Specimens in the Species Ephemerella invaria:

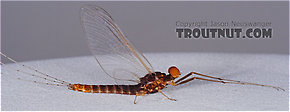

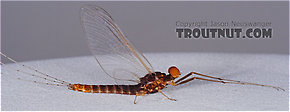

Male Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun) Mayfly Spinner View 12 Pictures

View 12 Pictures

View 12 Pictures

View 12 PicturesCollected June 3, 2005 from the Teal River in Wisconsin

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on May 24, 2006

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on May 24, 2006

Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun) Mayfly Nymph View 8 PicturesThis small Ephemerella invaria nymph was at least a month away from emergence.

View 8 PicturesThis small Ephemerella invaria nymph was at least a month away from emergence.

View 8 PicturesThis small Ephemerella invaria nymph was at least a month away from emergence.

View 8 PicturesThis small Ephemerella invaria nymph was at least a month away from emergence.Collected April 19, 2006 from the Beaverkill River in New York

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on April 21, 2006

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on April 21, 2006

Male Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun) Mayfly Dun View 7 Pictures

View 7 Pictures

View 7 Pictures

View 7 PicturesCollected May 26, 2007 from Penn's Creek in Pennsylvania

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on June 4, 2007

Added to Troutnut.com by Troutnut on June 4, 2007

15 Underwater Pictures of Ephemerella invaria Mayflies:

There's a large Ephemerella subvaria nymph in the top left.

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun), Insect Order Trichoptera (Caddisflies), and Mayfly Species Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson).

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun), Insect Order Trichoptera (Caddisflies), and Mayfly Species Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson).

StateWisconsin

LocationNamekagon River

Date TakenMar 20, 2004

Date AddedJan 25, 2006

AuthorTroutnut

CameraOlympus C740UZ

The white blotches on this rock are Leucotrichia caddisfly cases, and the wispy tubes are cases made by a type of midge.

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun), Caddisfly Species Leucotrichia pictipes (Ring Horn Microcaddis), and True Fly Family Chironomidae (Midges).

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun), Caddisfly Species Leucotrichia pictipes (Ring Horn Microcaddis), and True Fly Family Chironomidae (Midges).

StateWisconsin

LocationNamekagon River

Date TakenMar 24, 2004

Date AddedJan 25, 2006

AuthorTroutnut

CameraOlympus C740UZ

Some large Ephemerella mayfly nymphs cling to a log. In the background, hundreds of Simuliidae black fly larvae swing in large clusters in the current.

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson), True Fly Family Simuliidae (Black Flies), and Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun).

In this picture: Mayfly Species Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson), True Fly Family Simuliidae (Black Flies), and Mayfly Species Ephemerella invaria (Sulphur Dun).

StateWisconsin

LocationNamekagon River

Date TakenMar 20, 2004

Date AddedJan 25, 2006

AuthorTroutnut

CameraOlympus C740UZ

Recent Discussions of Ephemerella invaria

rotunda 8 Replies »

Posted by CharlieBugs on Jan 26, 2015

Last reply on Feb 1, 2015 by Gutcutter

Your post on Ephemerella subvaria brought back some memories that might be of interest to some readers.

I got my master’s degree under Ed Cooper at Penn State in 1966. I studied the impact of low oxygen from Penn State’s sewage plant on the mayflies of Spring Creek. The plant mostly removed BOD (organic matter which causes low oxygen) by oxidizing it in a bacteria rich environment. But at that time the plant did not remove phosphorus (and nitrogen) which fertilized the macrophytic algae and other plant growth. There were far more macrophytes (large plants) in Spring Creek below the sewage plant entrance than above, and essentially no mayflies. What was there in the effluent that killed the mayflies? Mayflies put directly in the effluent did not die over a 16 hour day. But oxygen samples taken over 24 hours in summer showed a much greater variation below the effluent (from 16 ppm (or mg/l), 160% of saturation in late afternoon) to 3 ppm (30 percent saturation just before dawn) (vs 14 to 10 ppm, +- 20 percent saturation above the effluent.

I built a Rube Goldberg machine in the lab that would control the oxygen levels and temperature of control and experimental cages that each held 25 mayflies. The control would keep oxygen near saturation and the experimental one would lower the oxygen over 8 hours (the length of night in summer). Mortality was dependent upon both oxygen level and temperature. Virtually no mayflies would die if the oxygen was above 2 PPM (or mg/l) at 8 C, or at 4.5 at 20 C. Seventy five percent of larvae would die at 1 ppm at 8 degrees and 2.5 ppm at 20 degrees. So the mortality was much more if the temperatures were high. Hence most of the mortality would presumably occur in August when the high temperatures (20C) would increase the larvae metabolism and hence need for oxygen, but the water would hold less oxygen even before the night-time respiration of the macrophytes would reduce it much further (to only 3 ppm). Thus the low nighttime oxygen caused by excessive plant growth was a sufficient cause or the near total absence of mayflies below the sewage plant. Recognizing the aquatic impact Penn State started to use land disposal of its effluent which as far as I knew alleviated, and even stopped, the negative impacts on the mayflies. Can anyone verify this ? The otherwise well done “The Fishery of Spring Creek; A Watershed Under Siege “

By Robert F. Carline, Rebecca L. Dunlap Jason E. Detar, Bruce A. Hollender Has nothing on dissolved oxygen or aquatic insects. In my opinion we need much more of an ecosystems approach for streams (Which we are doing for Little Sandy Creek in N.Y.).

Now back to Ephemeralla subvaria. The title of the paper I published on this project (my first of nearly 300 publications) was:

1. Hall, C.A.S. 1969. Mortality of the mayfly nymph, Ephemerella rotunda, at low dissolved oxygen concentrations. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 85(1): 34-39 (M.S. Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 1966).

Whoa! Ephemeralla rotunda? This was by far the most abundant mayfly in Spring Creek where I sampled! But I could not even find the name in your list. Also I had my samples verified by Burke, author of the authoritative "Mayflies of Illinois", and he said Well that’s what it keyed out to in my book”. (Talk about scientific ass covering! ) Well to make matters worse (as of 24 hours ago) my next girlfriend, Molly, at the University of North Carolina, loved the name of “Ephemerella rotunda”, the rotund one, which comes to think of it described her as well. I liked it too. But n’exist plus: where had the most abundant mayfly gone? Fortunately upon reading the rest of the post I found “Ephemerella invaria is one of the two species frequently known as Sulphurs (the other is Ephemerella dorothea). There used to be a third, Ephemerella rotunda, but entomologists recently discovered that invaria and rotunda are a single species with an incredible range of individual variation." Ahh neither rotunda nor Molly stood the test of time. So I assume what I called rotunda is still alive and well in Spring Creek as invaria. Again, can anyone verify that?

If anyone wants to follow up on the distribution and abundance of mayfly (or any other species) may I recommend: Hall, C.A.S., J.A. Stanford and R. Hauer. 1992. The distribution and abundance of organisms as a consequence of energy balances along multiple environmental gradients. Oikos 65: 377-390. I can send it if you cannot get it from google, which I think you can. (chall@esf.edu)

ReplyAw Shucks 10 Replies »I got my master’s degree under Ed Cooper at Penn State in 1966. I studied the impact of low oxygen from Penn State’s sewage plant on the mayflies of Spring Creek. The plant mostly removed BOD (organic matter which causes low oxygen) by oxidizing it in a bacteria rich environment. But at that time the plant did not remove phosphorus (and nitrogen) which fertilized the macrophytic algae and other plant growth. There were far more macrophytes (large plants) in Spring Creek below the sewage plant entrance than above, and essentially no mayflies. What was there in the effluent that killed the mayflies? Mayflies put directly in the effluent did not die over a 16 hour day. But oxygen samples taken over 24 hours in summer showed a much greater variation below the effluent (from 16 ppm (or mg/l), 160% of saturation in late afternoon) to 3 ppm (30 percent saturation just before dawn) (vs 14 to 10 ppm, +- 20 percent saturation above the effluent.

I built a Rube Goldberg machine in the lab that would control the oxygen levels and temperature of control and experimental cages that each held 25 mayflies. The control would keep oxygen near saturation and the experimental one would lower the oxygen over 8 hours (the length of night in summer). Mortality was dependent upon both oxygen level and temperature. Virtually no mayflies would die if the oxygen was above 2 PPM (or mg/l) at 8 C, or at 4.5 at 20 C. Seventy five percent of larvae would die at 1 ppm at 8 degrees and 2.5 ppm at 20 degrees. So the mortality was much more if the temperatures were high. Hence most of the mortality would presumably occur in August when the high temperatures (20C) would increase the larvae metabolism and hence need for oxygen, but the water would hold less oxygen even before the night-time respiration of the macrophytes would reduce it much further (to only 3 ppm). Thus the low nighttime oxygen caused by excessive plant growth was a sufficient cause or the near total absence of mayflies below the sewage plant. Recognizing the aquatic impact Penn State started to use land disposal of its effluent which as far as I knew alleviated, and even stopped, the negative impacts on the mayflies. Can anyone verify this ? The otherwise well done “The Fishery of Spring Creek; A Watershed Under Siege “

By Robert F. Carline, Rebecca L. Dunlap Jason E. Detar, Bruce A. Hollender Has nothing on dissolved oxygen or aquatic insects. In my opinion we need much more of an ecosystems approach for streams (Which we are doing for Little Sandy Creek in N.Y.).

Now back to Ephemeralla subvaria. The title of the paper I published on this project (my first of nearly 300 publications) was:

1. Hall, C.A.S. 1969. Mortality of the mayfly nymph, Ephemerella rotunda, at low dissolved oxygen concentrations. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 85(1): 34-39 (M.S. Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 1966).

Whoa! Ephemeralla rotunda? This was by far the most abundant mayfly in Spring Creek where I sampled! But I could not even find the name in your list. Also I had my samples verified by Burke, author of the authoritative "Mayflies of Illinois", and he said Well that’s what it keyed out to in my book”. (Talk about scientific ass covering! ) Well to make matters worse (as of 24 hours ago) my next girlfriend, Molly, at the University of North Carolina, loved the name of “Ephemerella rotunda”, the rotund one, which comes to think of it described her as well. I liked it too. But n’exist plus: where had the most abundant mayfly gone? Fortunately upon reading the rest of the post I found “Ephemerella invaria is one of the two species frequently known as Sulphurs (the other is Ephemerella dorothea). There used to be a third, Ephemerella rotunda, but entomologists recently discovered that invaria and rotunda are a single species with an incredible range of individual variation." Ahh neither rotunda nor Molly stood the test of time. So I assume what I called rotunda is still alive and well in Spring Creek as invaria. Again, can anyone verify that?

If anyone wants to follow up on the distribution and abundance of mayfly (or any other species) may I recommend: Hall, C.A.S., J.A. Stanford and R. Hauer. 1992. The distribution and abundance of organisms as a consequence of energy balances along multiple environmental gradients. Oikos 65: 377-390. I can send it if you cannot get it from google, which I think you can. (chall@esf.edu)

OK, this is going to seem like a major duh experience for some of you, but the other night I found a sulphur spinner on the door of a bathhouse in a campground I was staying at. Looking for other bugs I then saw a pale nymph shuck on the door. I was totally confused. A nymph this far from the stream? Was this some alien bug? Looking closer I noticed that the shape was too slender for a nymph and that the wing pads were more like little protruding pockets--and it hit me. Spinner shuck. I knew that mayflies molted to produce a spinner, but I had thought the shuck would be more insubstantial--something that would be flimsy and lack form. This was so cool, and at the same time I felt so silly for thinking it could somehow have been a nymph shuck. It's the first spinner shuck I've seen, but I assume that I'll start seeing them everywhere now, like a new word you learn. Anybody else have a spinner shuck story?

ReplyHatching SulphurPosted by Martinlf on Oct 14, 2008

Click on "40 more specimens" and scroll down for one photo.

ReplyThere is 1 more topic.

Your Thoughts On Ephemerella invaria:

Top 10 Fly Hatches

Top Gift Shop Designs

Eat mayflies.

Top Insect Specimens

Miscellaneous Sites

Troutnut.com is copyright © 2004-2024 Jason

Neuswanger (email Jason). See my FAQ for information about use of my images.

privacy policy

privacy policy