Blog & Latest Updates

Fly Fishing Articles

Insects by Common Name

Dark Hendricksons

Scientific Names

Like most common names, "Dark Hendrickson" can refer to more than one taxon. They're previewed below, along with 12 specimens. For more detail click through to the scientific names.

Mayfly Species Ephemerella subvaria

These are often called Dark Hendricksons.

The Hendrickson hatch is almost synonymous with fly fishing in America. It has been romanticized by our finest writers, enshrined on an untouchable pedestal next to Theodore Gordon, bamboo, and the Beaverkill.

The fame is well-deserved. Ephemerella subvaria is a prolific species which drives trout to gorge themselves. Its subtleties demand the best of us as anglers, and meeting the challenge pays off handsomely in bent graphite and screaming reels.

The fame is well-deserved. Ephemerella subvaria is a prolific species which drives trout to gorge themselves. Its subtleties demand the best of us as anglers, and meeting the challenge pays off handsomely in bent graphite and screaming reels.

Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson) Mayfly Nymph View 7 PicturesThis is another unusual brown Ephemerella nymph. The "fan-tail" which defines the Ephemerella genus is particularly evident on this specimen.

View 7 PicturesThis is another unusual brown Ephemerella nymph. The "fan-tail" which defines the Ephemerella genus is particularly evident on this specimen.

View 7 PicturesThis is another unusual brown Ephemerella nymph. The "fan-tail" which defines the Ephemerella genus is particularly evident on this specimen.

View 7 PicturesThis is another unusual brown Ephemerella nymph. The "fan-tail" which defines the Ephemerella genus is particularly evident on this specimen.Male Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson) Mayfly Dun View 9 PicturesI collected this male Hendrickson dun and a female in the pool on the Beaverkill where the popular Hendrickson pattern was first created. He is descended from mayfly royalty.

View 9 PicturesI collected this male Hendrickson dun and a female in the pool on the Beaverkill where the popular Hendrickson pattern was first created. He is descended from mayfly royalty.

View 9 PicturesI collected this male Hendrickson dun and a female in the pool on the Beaverkill where the popular Hendrickson pattern was first created. He is descended from mayfly royalty.

View 9 PicturesI collected this male Hendrickson dun and a female in the pool on the Beaverkill where the popular Hendrickson pattern was first created. He is descended from mayfly royalty.Male Ephemerella subvaria (Hendrickson) Mayfly Spinner View 11 PicturesI collected this beautiful male Hendrickson specimen as a dun, along with a female Hendrickson from the same hatch. Both molted into spinners in my house within a couple of days.

View 11 PicturesI collected this beautiful male Hendrickson specimen as a dun, along with a female Hendrickson from the same hatch. Both molted into spinners in my house within a couple of days.

View 11 PicturesI collected this beautiful male Hendrickson specimen as a dun, along with a female Hendrickson from the same hatch. Both molted into spinners in my house within a couple of days.

View 11 PicturesI collected this beautiful male Hendrickson specimen as a dun, along with a female Hendrickson from the same hatch. Both molted into spinners in my house within a couple of days.See 31 more specimens...

Mayfly Species Ephemerella needhami

These are sometimes called Dark Hendricksons.

This small and slightly noteworthy mayfly appears during the finest hours of the year. Ernest Schwiebert describes an Ephemerella needhami day in Matching the Hatch:

I have not fished a needhami emergence, but the exquisite nymphs show up often (though never abundantly) in my samples.

"It was a wonderul morning, with a sky of indescribable blue and big, clean-looking cumulus clouds, and the water was sparkling and alive. You have seen the water with that lively look; you have also seen it dead and uninviting in a way that dampens the enthusiasm the moment you wade out into the current."

I have not fished a needhami emergence, but the exquisite nymphs show up often (though never abundantly) in my samples.

Ephemerella needhami (Little Dark Hendrickson) Mayfly Nymph View 6 PicturesI photographed three strange striped Ephemerella nymphs from the same trip on the same river: this one, a brown one, and a very very striped one. I have tentatively put them all in Ephemerella needhami for now.

View 6 PicturesI photographed three strange striped Ephemerella nymphs from the same trip on the same river: this one, a brown one, and a very very striped one. I have tentatively put them all in Ephemerella needhami for now.

View 6 PicturesI photographed three strange striped Ephemerella nymphs from the same trip on the same river: this one, a brown one, and a very very striped one. I have tentatively put them all in Ephemerella needhami for now.

View 6 PicturesI photographed three strange striped Ephemerella nymphs from the same trip on the same river: this one, a brown one, and a very very striped one. I have tentatively put them all in Ephemerella needhami for now.Ephemerella needhami (Little Dark Hendrickson) Mayfly Dun View 7 PicturesSee the comments for an interesting discussion of the identification of this dun.

View 7 PicturesSee the comments for an interesting discussion of the identification of this dun.

View 7 PicturesSee the comments for an interesting discussion of the identification of this dun.

View 7 PicturesSee the comments for an interesting discussion of the identification of this dun.See 7 more specimens...

Mayfly Species Leptophlebia cupida

These are very rarely called Dark Hendricksons.

Most anglers encounter these large mayflies every Spring in the East and Midwest. They are omnipresent in small portions, providing filler action in the days or hours between the prolific hatches of the early season Ephemerella flies.

See the main Leptophlebia page for details about their nymphs, hatching, and egg-laying behavior. This is by far the most important species of that genus.

See the main Leptophlebia page for details about their nymphs, hatching, and egg-laying behavior. This is by far the most important species of that genus.

Male Leptophlebia cupida (Borcher Drake) Mayfly Dun View 6 PicturesThis Leptophlebia cupida dun was extremely cooperative, and it molted into a spinner for me in front of the camera. Here I have a few dun pictures and one spinner picture, and I've put the entire molting sequence in an article.

View 6 PicturesThis Leptophlebia cupida dun was extremely cooperative, and it molted into a spinner for me in front of the camera. Here I have a few dun pictures and one spinner picture, and I've put the entire molting sequence in an article.

View 6 PicturesThis Leptophlebia cupida dun was extremely cooperative, and it molted into a spinner for me in front of the camera. Here I have a few dun pictures and one spinner picture, and I've put the entire molting sequence in an article.

View 6 PicturesThis Leptophlebia cupida dun was extremely cooperative, and it molted into a spinner for me in front of the camera. Here I have a few dun pictures and one spinner picture, and I've put the entire molting sequence in an article.See 14 more specimens...

Mayfly Species Teloganopsis deficiens

These are very rarely called Dark Hendricksons.

Anglers in western Wisconsin, where these little flies hatch in good numbers on summer rivers, have termed them "Darth Vaders" because of the very dark color of their wings.

Until recently, this species was known as Serratella deficiens.

Until recently, this species was known as Serratella deficiens.

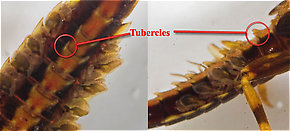

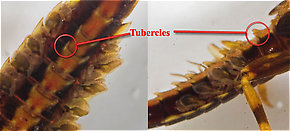

Teloganopsis deficiens (Little Black Quill) Mayfly Nymph View 6 PicturesThis nymph has tiny, barely detectable tubercles (

View 6 PicturesThis nymph has tiny, barely detectable tubercles ( Tubercle: Various peculiar little bumps or projections on an insect. Their character is important for the identification of many kinds of insects, such as the nymphs of Ephemerellidae mayflies.) on its abdominal segments, and I could not find the maxillary palpi. I have tentatively guessed that it is Serratella deficiens.

Tubercle: Various peculiar little bumps or projections on an insect. Their character is important for the identification of many kinds of insects, such as the nymphs of Ephemerellidae mayflies.) on its abdominal segments, and I could not find the maxillary palpi. I have tentatively guessed that it is Serratella deficiens.

View 6 PicturesThis nymph has tiny, barely detectable tubercles (

View 6 PicturesThis nymph has tiny, barely detectable tubercles (

A few (not all) of the abdominal tubercles on this Ephemerella needhami nymph are circled. They are especially large in this species.

Mayfly Species Ephemerella excrucians

These are very rarely called Dark Hendricksons.

For trout (if not anglers), this single species is arguably the most important mayfly in North America. In terms of sheer numbers, breadth of distribution and hatch duration, it has a good argument.

Ephemerella excrucians or Pale Morning Dun usually follows its larger sibling Ephemerella dorothea infrequens with which it shares the same common name. What it often lacks in size by comparison is made up for with it's duration, often lasting for months with intermittent peaks. This close relationship with infrequens has led many anglers to confuse Pale Morning Dun biology with that of the multivoltine (Multivoltine: Having more than one generation per year.) Baetidae species, having disparate broods that decrease in size as the season advances. Sharing the same common name has not helped to alleviate this misconception.

Until recently, Ephemerella excrucians was considered primarily an upper MidWestern species of some regional importance commonly called Little Red Quill among other names. Recent work by entomologists determined that it is actually the same species as the important Western Pale Morning Dun (prev.Ephemerella inermis), and the lake dwelling Sulphur Dun of the Yellowstone area, (prev.Ephemerella lacustris). Since all three are considered variations of the same species, they have been combined into excrucians, being the original name for the type species reported as far back as the Civil War. Angler speculation had simmered for some time that the stillwater loving Ephemerella lacustris was much more widespread, inhabiting more water types then previously thought and could account for many large sulfurish ephemerellids found in still to very slow water locations throughout the West. With the revisions, this discussion is now moot.

Ephemerella excrucians variability in appearance, habitat preferences, and wide geographical distribution are cause for angler confusion with the changes in classification. They can be pale yellow 18's on a large Oregon river, creamy orange 14's on western lakes and feeder streams, large olive green on CA spring creeks as well as tiny sulfur ones in many Western watersheds. Then there's the little Red Quill on small streams in Wisconsin. Yet, all are the same species.

Ephemerella excrucians or Pale Morning Dun usually follows its larger sibling Ephemerella dorothea infrequens with which it shares the same common name. What it often lacks in size by comparison is made up for with it's duration, often lasting for months with intermittent peaks. This close relationship with infrequens has led many anglers to confuse Pale Morning Dun biology with that of the multivoltine (Multivoltine: Having more than one generation per year.) Baetidae species, having disparate broods that decrease in size as the season advances. Sharing the same common name has not helped to alleviate this misconception.

Until recently, Ephemerella excrucians was considered primarily an upper MidWestern species of some regional importance commonly called Little Red Quill among other names. Recent work by entomologists determined that it is actually the same species as the important Western Pale Morning Dun (prev.Ephemerella inermis), and the lake dwelling Sulphur Dun of the Yellowstone area, (prev.Ephemerella lacustris). Since all three are considered variations of the same species, they have been combined into excrucians, being the original name for the type species reported as far back as the Civil War. Angler speculation had simmered for some time that the stillwater loving Ephemerella lacustris was much more widespread, inhabiting more water types then previously thought and could account for many large sulfurish ephemerellids found in still to very slow water locations throughout the West. With the revisions, this discussion is now moot.

Ephemerella excrucians variability in appearance, habitat preferences, and wide geographical distribution are cause for angler confusion with the changes in classification. They can be pale yellow 18's on a large Oregon river, creamy orange 14's on western lakes and feeder streams, large olive green on CA spring creeks as well as tiny sulfur ones in many Western watersheds. Then there's the little Red Quill on small streams in Wisconsin. Yet, all are the same species.

Ephemerella excrucians (Pale Morning Dun) Mayfly Nymph View 5 PicturesI spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) a while with a microscope to fairly positively identify this specimen as Ephemerella excrucians.

View 5 PicturesI spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) a while with a microscope to fairly positively identify this specimen as Ephemerella excrucians.

View 5 PicturesI spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) a while with a microscope to fairly positively identify this specimen as Ephemerella excrucians.

View 5 PicturesI spent (Spent: The wing position of many aquatic insects when they fall on the water after mating. The wings of both sides lay flat on the water. The word may be used to describe insects with their wings in that position, as well as the position itself.) a while with a microscope to fairly positively identify this specimen as Ephemerella excrucians.See 19 more specimens...

Top 10 Fly Hatches

Top Gift Shop Designs

Eat mayflies.

Top Insect Specimens

Miscellaneous Sites

Troutnut.com is copyright © 2004-2024 Jason

Neuswanger (email Jason). See my FAQ for information about use of my images.

privacy policy

privacy policy